Conducted over email from June 5 to June 10, 2023

Nick Sturm: You and I have talked before about your out-of-print works being republished, like Tell Me Again and even Alma, or The Dead Women, and there’s been this wave of efforts to do this for your poetry, like the new edition of Songs for the Unborn Second Baby from Distance No Object and Manhattan Luck from Hearts Desire Press for the Alette in Oakland events. You’ve said that Early Works has generated a lot of feeling while also bringing you back to something about yourself. What has Early Works been doing for you as you’ve been reading from and talking about it?

Alice Notley: Early Works causes me to remember who I was writing them, so that’s my life circumstances, my inexperience at living as a human, my relative lack of poetic skills—though I can see I was skilled. I am remembering how deeply I felt during the writing of certain of the poems, it’s a depth of satisfaction that isn’t like any other—not sensual or triumphant over others, and I can’t get the right name for it at this moment. I’ve described it before, when talking about the writing of 165 Meeting House Lane, as a meeting of sense of artistic form and sense of reality, real life inner and outer. The form of poetry achieves that. I’m remembering that feeling but also seeing what I didn’t know, how young I was, how I didn’t know what was going to happen in my life, to me and others—then some of it is happening, and I don’t know the future but maybe I do. I am trying to be something I’m not sometimes, I’m not facing up to the fact that I’m just not normal, and there is no quotidian (there never really was in the real New York School), though there is love. Some of the things I say almost rotely turn out to be so true! There is no money, and there will be no money, and that will be truer and truer. When I was young I thought everyone knew some poetry, knew poetry was a wonderful and noble pursuit, knew that they needed art. My parents, who couldn’t afford to go to college and in my father’s case finish high school, respected poetry and knew some. Now I know that most of the people in the world don’t even read books, though the illiterate often know more poetry than the educated do. But the countries I live in don’t really give a fuck if poetry exists or not, on the whole. But I see her, who I was, finding out she would write poetry and hoping she would get better at it and doing it blindly . . . I remember just pushing at it all the time, knowing it was the most important thing in the world. I’m still like that. She is very very present on the page and in each poem and word – that presence is so much of why the poems are good, so she’s embarrassing! She is unbelievably gauche and open and also very tough.

NS: It occurs to me that I’ve never asked you about the title For Frank O’Hara’s Birthday, the last book in Early Works. You wrote those poems in Wivenhoe, Essex, which is this quaint little village outside Colchester in England where Ted was teaching at the University of Essex in 1973-74. So much happened to you and your poems there, too. I went to Wivenhoe once and there were hollyhocks everywhere.

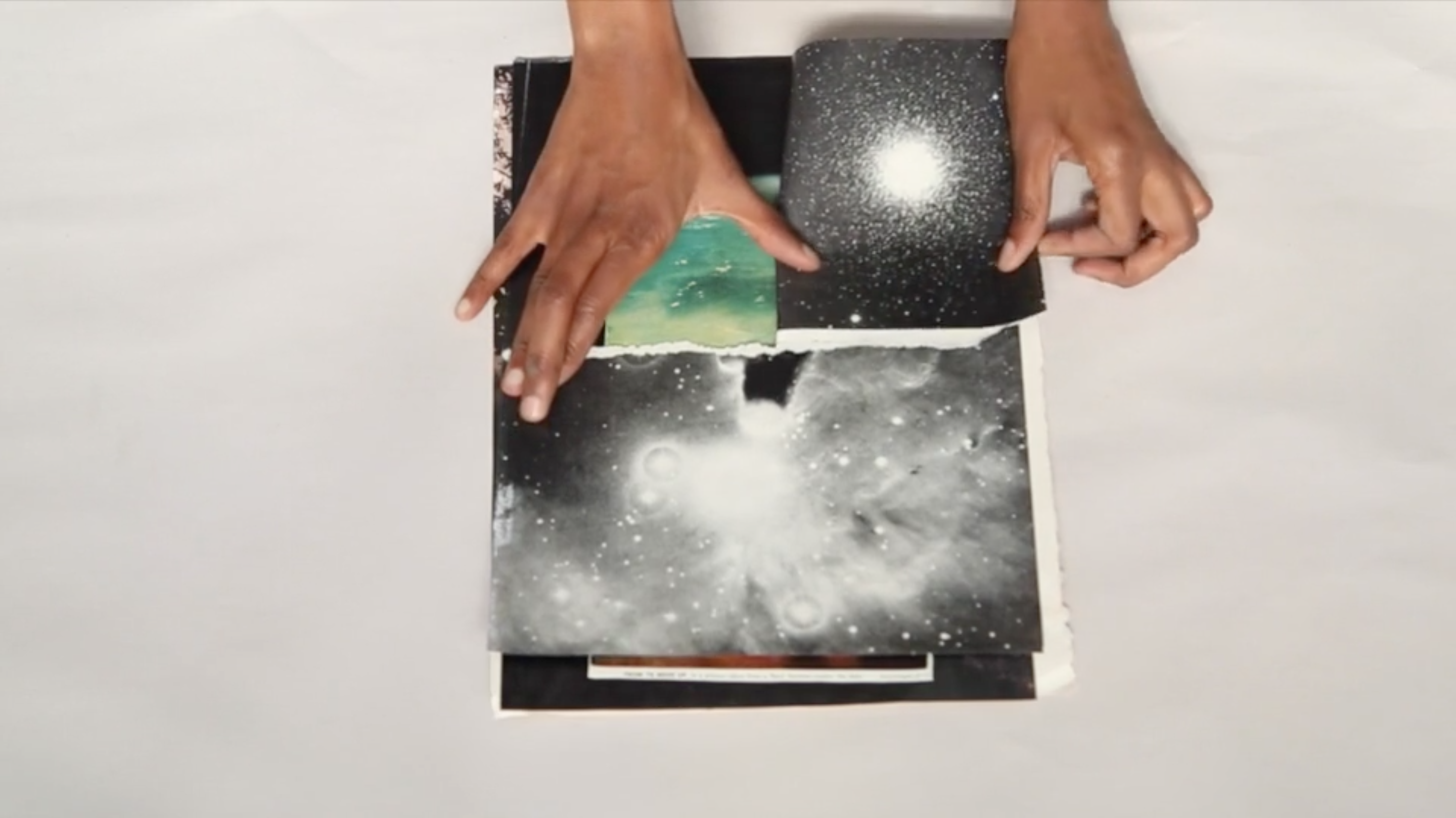

AN: I think Ted suggested the title, probably among many suggestions, since that is always a favorite game for poets and often with more than one participant. I probably chose it for a couple of reasons. One being that it made a flat horizontal line—speaking abstractly—to this slightly unruly herd of poems that make up the book. It’s almost opaque in relation to them but provides an umbrella anyway. However, you might consider the real title to be In Memory of My Feelings, I mean I built up to a place like that though not that form: Songs for the Unborn Second Baby, written at almost exactly the same time, is more in that form, as form and sound on the page. But something like “Your Dailiness,” that’s a subject-matter moment that relates to “In Memory of My Feelings.” Everything you’ve gone through, and then you arrive at a point of freedom. Songs for the Unborn Second Baby is actually an imitation of the form of O’Hara’s Odes, so you’ll understand that I was often working out in what I conceived to be O’Hara’s forms. The collected O’Hara had come out, and I was fascinated by the form of the poems in relation to each other as laid out in that volume. I loved the collage-like effect of all the forms he tried out, and the way the minor and major poems play off against each other. I thought quite consciously that I wanted to make work like that, even a very long work based on such a conception; I had the texture or feel of O’Hara’s collected, as a whole form, in my head as a goal for much of the ’70s.

NS: What’s it been like to have Early Works come out simultaneously with this new book, The Speak Angel Series? I know this wasn’t the plan originally, it was going to be The Speak Angel Series by itself. Then Jeff Alessandrelli at Fonograf Editions imagined a “First Four Books of Alice Notley,” and brought me on board, which led to Early Works. I’m still reading Speak Angel but recognize a series of networks between these poems and your poems from fifty years ago.

AN: The Speak Angel Series is in fact a play of different forms set against each other, though longer forms for the most part, but as I say that I realize . . . For example, in Book I, The House Gone, there are three kinds of forms set off against each other, a long-line narrative, increasingly snaky short-line stanzas that change the sound of the narrative from time to time, and actual inset poems of various lengths and titles. Book IV, To Paste On, contains works of all shapes and sizes, though the narrative is maintained. But with references to actual current events, most of the book being “mythic” or some word like that. And in each of the other four books I find ways to create variety in the surface and form I’ve chosen. I’ve worked like that probably since the early ’70s, and as a method it is probably related to my love of the O’Hara collected. But there are other kinds of networks between Early Works and The Speak Angel Series. Any time I give a reading from the two I notice the same words even, the same preoccupations, the Samson dream! I was still dreaming I was Samson fifty years later! Obviously I was always destined to tear this building down. I’m comforted by the fact that I can see these connections, that they’re real, that I’ve in some sense always known who I was and what I was doing, even if unconsciously. Everything I learned how to do as a young poet in the prevalent lyric-I mode, all the forms I played with and perhaps mastered, are subsumed into the overall structure and sound of my later books. I just did it, and I’m just doing it now. I know what I’m doing, but if I have a very deliberate map I won’t want to take the trip. Later I see that everything is in place as if by magic.

NS: At the symposium on your work in Paris last April you said a few things about form, and someone actually said it was surprising for them to think of you as a formal poet. You said: “We are condemned to form.” You also said, linking form with matter, “Somehow matter chose to exist.” You’re talking about poems but also the forms that are our selves. I remember this part of the conversation ended with you asking, “What can we learn from the fact that we don’t die?” Are you still thinking about this question? About form and matter in these ways?

AN: Yes, I seem to be writing a continuous work now dealing with this subject. I’m currently wondering how to divide it into books for publication, the outer form changes constantly and I might be inside a sub-form for quite a while without remembering what I originally set out to do. Chronology seems to be abolished, and I’m currently confused. Essentially I’m questioning every single thing taken for granted about the existence of matter, what it is like, whether or not one is actually part of the matter system that everyone says one is. Time and so on. I call myself god, since it feels as if human society needs a new definition of what that might be, I say god is powerless, since power is a human conception and doesn’t apply anywhere else in the universe. And so on. I say that humans don’t die, but there is no judgment or justice in the afterlife because that’s also human bullshit, no reincarnation either into some cruel class system. I constantly say that the planet is teensy, and all planets are teensy, and that the reason you don’t fall off these little golf balls is that I hold them and you up, being gravity. Things like that. As I write these works I become more and more powerless, my knees are going, I just started blood pressure medicine, I have my annual cancer checkup coming up.

NS: Is there a place where you do draw power from?

AN: I think I’m saying that in the Real World there is no power. Power is what bodies do to each other. It’s kind of disgusting. I must be proposing a love that isn’t power. There is a sort of electricity I experience though when I read poetry aloud, I suppose also when I write it but that’s more flowing. So, yes, the power to light up!

NS: That reminds me of a line in Book I of The Speak Angel Series from “The Woman Who Counted Crossties”: “I promise you love at the very least that of the great words and me.” When I’m reading a long work like Speak Angel, and how I remember reading Disobedience and Benediction, it’s almost like reading a mystical text. Not that they are those types of texts but reading them is this incremental process of brief or sustained absorptions into “great words and me.” I read Kerouac’s The Book of the Dharma like this one summer, collaging it into what else I was adjacent to. It’s always incredible, while reading, to imagine how writing with this type of duration comes into being. In your preface for Speak Angel you give a gloss for each book’s form and content, but what was the composition process for the entire project? Did it change, for instance, when you got to tracing the form of The Descent of Alette in Book VI, The Poem? Was it startling to suddenly be back in the Alette form?

AN: Actually, no. I was in an entirely other kind of place from when I wrote Alette . . . I’m still not clear why I did that, except to make a balance with Book III which is in the measure, sort of, but not the overall form book by book of Alette. When I began Speak Angel in 2013, I had no idea except for long lines. The file for the first book was called “Long Lines.” I say what I’m going to do at the beginning of that book—unlike with others of my book-length works, I wrote the beginning at the beginning. Then I wrote daily slowly drawing out the story of the woman and the variant story, as told by my father—he used to tell me stories sometimes, particularly one that was about a house, the house whose loss is behind Book I, The House Gone. Because when I was seven he stopped ever taking us for a car ride in the evening as he used to, and I would beg and he would say: Once there was a man who took his family for a ride every evening because he didn’t have a nice house to be at home in in the evening, and then he built one and he didn’t need to go for a ride anymore! I think I was thinking of that, and how after my mother died we, my siblings and I, very quickly had to dismantle everything in that house and make it ready to sell. I don’t have room to tell all this, it is, though, my childhood house, The House Gone. My house was finally gone and I realized I was in fact supposed to lead all the dead and living, in this poem, to a certain place in the cosmos out in the open without houses. I realized I had to change the universe or cosmos or whatever one would call it. So I did this inventing ways to keep the surface of the poem interesting, and one arrived. But I know that one never arrives, that isn’t Ever what’s going on in existence, which is forever. The cosmos is chaotic, more like the ancient perception of chaos than something like a mess. It isn’t mess, it’s the random creation of moments, not linear, and many many at the same time. So I was going to continue and keep refinding the meaning of the point we had arrived at and what we were doing. Book II, Opera, turned out to be an opera, a singing of further understanding of this new origination which involves collaging and pasting, since there is never nothing to make something out of. So that is sung. In Book III, Healing Matter, the fact that in the previous book we were all standing on ice at the edge of an abyss caught up with me, the writer, and I realized I had to do something about a landscape. So I proposed to explore the abyss, and doing that it seemed natural to revive the Alette measure since it was conceived for a poem of levels of places. However, I began to refer to friends of mine—my family was already involved, and then Michael Brown was shot and killed in Ferguson, Missouri. I don’t name him yet, but someone is suddenly shot and killed while I am going about the poem. In Book IV, To Paste On, I have decided to make a place for different kinds of forms so I can deal with Michael’s death and situation and also other events in the world out there—Ebola, and the Syrian Civil War, for example. I also ended up writing several long, long-lined, almost sermon-like works. Then I thought I really did need to use a collage form, since collaging, pasting-on was continuously referred to as the way the new universe was being made. So I wrote the next book, Book V, Out of Order, in a black notebook, maybe two, those black leather-bound sketchbooks with blank paper, not proceeding consecutively but skipping around in the notebook, writing the “story” randomly, and in the typing up often rearranging lines, getting my head into a place during composition, as well, where I could “get” the lines out of order, receive them that way. Then I wrote the final book calling it The Poem. As if it were what I had been aiming for, and did all of that Alette tracing (a good word for it). The outer world stays with me, but it becomes incorporated more and more into the story, people from the news become characters, but that isn’t the correct way to put it: I spoke to them and had visions with them. It always felt very real.

NS: These two incredible new books are out from Fonograf. Runes & Chords was published by Archway Editions. Your book of selected talks and essays, Telling the Truth as It Comes Up, is forthcoming with The Song Cave later this year. You just read in London, you’re going to Berlin, and then coming back to the States soon. What do you want to do next? I’m suddenly thinking of how you ended your preface to Early Works, how moved I was reading it for the first time: “And once more, I thank Ted, who is somewhere.” Where do you want to go in your poems? Where will you go?

AN: First I should say that a new book from Penguin is going into production, called Being Reflected Upon. The title is taken from a line by Frank O’Hara. The first poet I loved, and Ted, and Doug, are and will always be inside whatever happens. As well, Anselm and Edmund, those great poets. Being Reflected Upon is dedicated to Anne Waldman, and it contains references and anecdotes and specific human connection throughout. It also provides a practical connection to The Speak Angel Series and to what I think I know about what’s going on metaphysically and also how to go on. Which seems to be what everyone is asking: how do we go on? And as Frank said Samuel and Pierre said we shall continue what else is there to do? Nothing disappears, and everything comes back. So I will continue working on my knowledge, my poetry, my stories. I will continue to be interviewed, since I do a lot of my thinking when people ask me questions. I will be here, or somewhere, the next time anyone comes through.