Saretta Morgan: My introduction to your practice was through your video, Drafts. Now, at this point, having experienced more of your work, I think about how Drafts typifies the different ways that iteration takes place across your practice. What I appreciate about these particular “drafts” is that their progression doesn’t feel developmental. Rather, they are all the groundwork of each other. Every time the frame resets there’s an opportunity for the text and images to offer something that neither neatly extends nor contradicts what came before. Can you talk about how you understand multiplicity as it relates to landscape?

Dionne Lee: A lot of my work is a response to the ways landscape photography has historically represented places, most specifically the American landscape. The historical view (literally) has been distant, wide-angled, dominant (looking down onto land or across a vast vista). These perspectives are inseparable from (and motivators of) manifest destiny and colonization.

I made Drafts in graduate school as I was trying to understand my own relationship to place (after moving to California from New York City where I was born and raised). It was a disorienting time, not just because I was acclimating to a new environment—I couldn’t reconcile the historical patterns of landscape photography. I knew I wanted to make work about land but I wasn’t sure where my perspective should begin. In the last few years I’ve often described part of my practice as “staying close to the ground.” This is literal (my camera is often pointed down, I don’t drive I walk, I collect rocks and sticks for my work…), it is also a pedagogy—a way I teach myself to resist the perspective of ownership, control, and dominance. To resist “documentation” and just look.

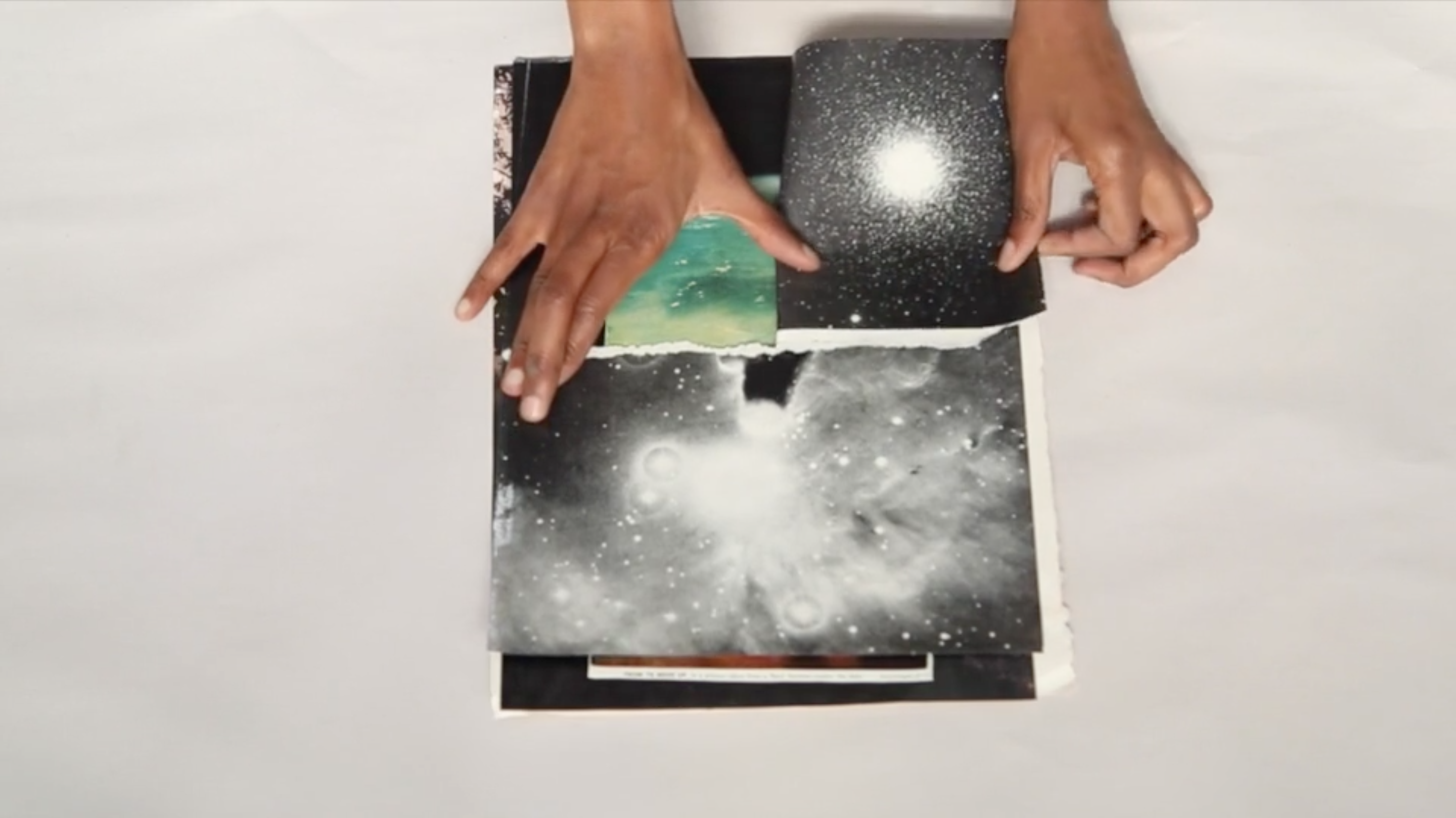

The video is mostly improvised. In some ways I was definitely working through my frustration with landscape photography and how to make my own images (I honestly think I’ve only made one “landscape photograph”: A Test for 40 Acres). However, I think Drafts ended up being more of a liberatory exercise than a reckoning (there is nothing I wanted/want to settle or make sense of/justify in terms of the traditions of landscape photography). Improvisation made space for the impulse to tear through images and create new, fleeting, scapes. In large part the title comes from this… the assemblages are drafts (I also hadn’t actually made a collage yet and was TERRIFIED of gluing things together! For real). Multiplicity, for me, is a way to remember that land itself is limitless. It is old and layered and always changing. It changes at different speeds at the same time: seasonally we can see a landscape go through changes, geologically we can’t. I love knowing there are ways in which the land shape-shifts that I will never be able to witness. Lately I’ve been spending a lot of time looking at geology books and fossils and thinking about all those layers.

SM: I appreciate the tension that fossils produce alongside the recognition of change you’re incapable of witnessing. It gives each fossil a poetic quality. As in, they become responsible for expressing a great deal. They are each fully their own expression of life and an origin story at once.

I wonder if you could share about what you understand your origins to be as an artist, and more generally as a person who thinks, and feels, and holds an investment in the way living takes shape.

DL: Yes. Well, my dad is an artist and my grandfather (his dad) was a hobby photographer who built a darkroom in a closet in the apartment my dad grew up in. It’s… pretty wild. I’m actually having a hard time with this question! Partly because family stuff can be weird (though a very special lineage to be part of), but also it feels like a very big question that maybe I am trying to squeeze too tight. It feels related to my role as a teacher. I really believe the normative ways we’ve shown and practiced “investment” in the world around us is limiting and can be destructive (it serves capitalism) when not partnered with self-discovered knowledge, experience as research, and a circular (as opposed to top-down/dictated) way of sharing knowledge. So part of me sees my origins as an artist as a deeply political and spiritual choice… I really believe in the circle! Another part of me, says: I know no other way! Artists are researchers and this is how I research best. And I think everyone should learn to research in this way too.

I really like this question and am going to think about it more. I’ve definitely thought about it in the past…but it’s kind of a scary place to go…! In a not-bad way. I appreciate it.

SM: I was sitting with your response this weekend. And also listening to an interview between David Naimon and Christina Sharpe on her recent book, Ordinary Notes. Sharpe talked about receiving the practice of reading, as well as the practice of cultivating beauty, from her mother. And her understanding that beauty wasn’t something that was “passively received,” but was an intentional methodology. I think that resonates with what you’ve begun to share about 1) experiential knowledge and how we learn to invest in the world, and 2) your question of where you wanted your own perspective/orientation as a person making work about land to begin.

When I think about your photography, I do feel called to think about landscape as a process of navigation. One that’s generative. One that requires improvisation. One that’s inherently speculative. How would you say that you’ve developed (or are developing) a personal landscape methodology?

DL: I was actually listening to that very interview as I was doing some spring cleaning before leaving for my trip. It was such a full conversation. As I was listening, I knew I’d need to re-listen several more times.

Central to my process and research (/methodology) is what I mentioned earlier about staying close to the ground and those literal practices of walking and the orientation of my camera, etc. as a way to develop a fuller and more intimate understanding of a place and my relationship to it. It’s related to the practice of “ground truthing” (which I’m familiar with through the work of Aurora Tang, Program Director for the Center of Land Use Interpretation, who I will spend some time with this fall), in which a first-person encounter is the base for other forms of knowledge and information to be integrated.

SM: If I think of what you’ve outlined, and Tang’s “ground truthing,” as processes for regarding landscape—and I understand that you’re moving against documentation, control, and perspectives of ownership—I wonder how/when you come to know that a particular process or frame (being close to the ground, for instance) is what a moment or space calls for you to practice in order to experience intimacy. What are the governing principles (or to move with your terms: the guiding politic? or spiritual impetus?) behind why you regard in the way that you regard?

DL: I think every space requires the process/experience of being close to the ground/ground truthing/etc. Not only to develop a sense of intimacy, but a sense of knowing (not in the complete sense, maybe like one or two prongs if one is lucky!).

I think my guiding principle is understanding the limits of knowing not as a hindrance or something to aspire to (all-knowing) but a sense of freedom, intimacy, respect, and possibility. I think of Walking by Linda Hogan.

SM: Oh, yes! Freedom, intimacy, and respect. For me those alignments are the conditions for pleasure. And pleasure is a huge part of your work for me. It’s a similar experience to the pleasure I feel when I’m reading. You know those moments when you encounter words that you couldn’t have put together yourself (at least not yet) but which clearly illuminate something you recognize as existing inside of yourself and also reflecting how you understand the world around you to be. The pleasure of recognizing what you feel.

Thank you for bringing in Linda Hogan. Yes. Walking animates—through foliage and corpse and hillsides—the process you’ve gracefully shared. And actually, I’m going to take my next question from her closing lines: “Walking, I am listening to a deeper way. Suddenly all my ancestors are behind me. Be still, they say. Watch and listen. You are the result of the love of thousands.”

There’s such gorgeous attention in her narrative to what plays out materially through desire and competition, and the affective consequences of existing in the presence of “many gods [who] love and eat one another.” I appreciate that Hogan’s capacity to discern the interplay/movement/relationality is tied to kinship. In her words: “…a kind of knowing inside me, a kinship and longing…”

When you’re walking (both literally, and in other expressions of grounding), for whom (or what) are you listening?

DL: My walks (research walks, I suppose) often take the style of a dérive (loosely). That said, I am not limiting the act of listening to sound alone. I’m listening to the terrain, what paths may appear, or thinking how I can forge my own (in a literal sense as going off-trail, or in urban environments taking alleys as opposed to main roads).

I am also listening to myself, which is also listening to the ancestors I suppose. In my earlier work I thought a lot about how to bridge the gap I was experiencing between myself and my environment. A bridge is built through reassurance, and the truth of the fact that connection to land and place has been a long-term formation that has happened generationally for all of us. This collective dissociation from the environment actually feels like a recent phenomenon (of course, I am not talking about when people are forcibly and/or violently displaced from their environment). It’s as if we are undoing some of that generational wayfinding. There is such a difference in learning to know a place by wandering, or even looking at a map and trying to remember how to navigate in real time, versus having the Google Maps voice direct each step for you (funny to think about that as a form of “listening”!).

I want to also say that listening itself is the guide/navigator. There is so much to listen to if you are really paying attention with all senses. I guess sometimes it’s hard to choose!