In Robert Glück’s 1985 novel Jack the Modernist, his narrator considers C. Allen Gilbert’s Victorian painting “All is Vanity”: an agamograph that is at one angle, a skull, and at another, a woman staring into a vanity. The narrator, a gay man living in 1981 San Francisco, wants his bathhouse orgasm to “fall between those images. That’s not really a place.” The pleasure of Glück’s newest collection, I, Boombox (Roof Books), a modernist life poem, locates itself in this same in-between place, where a slip of the eye or ear unveils a wholly new image.

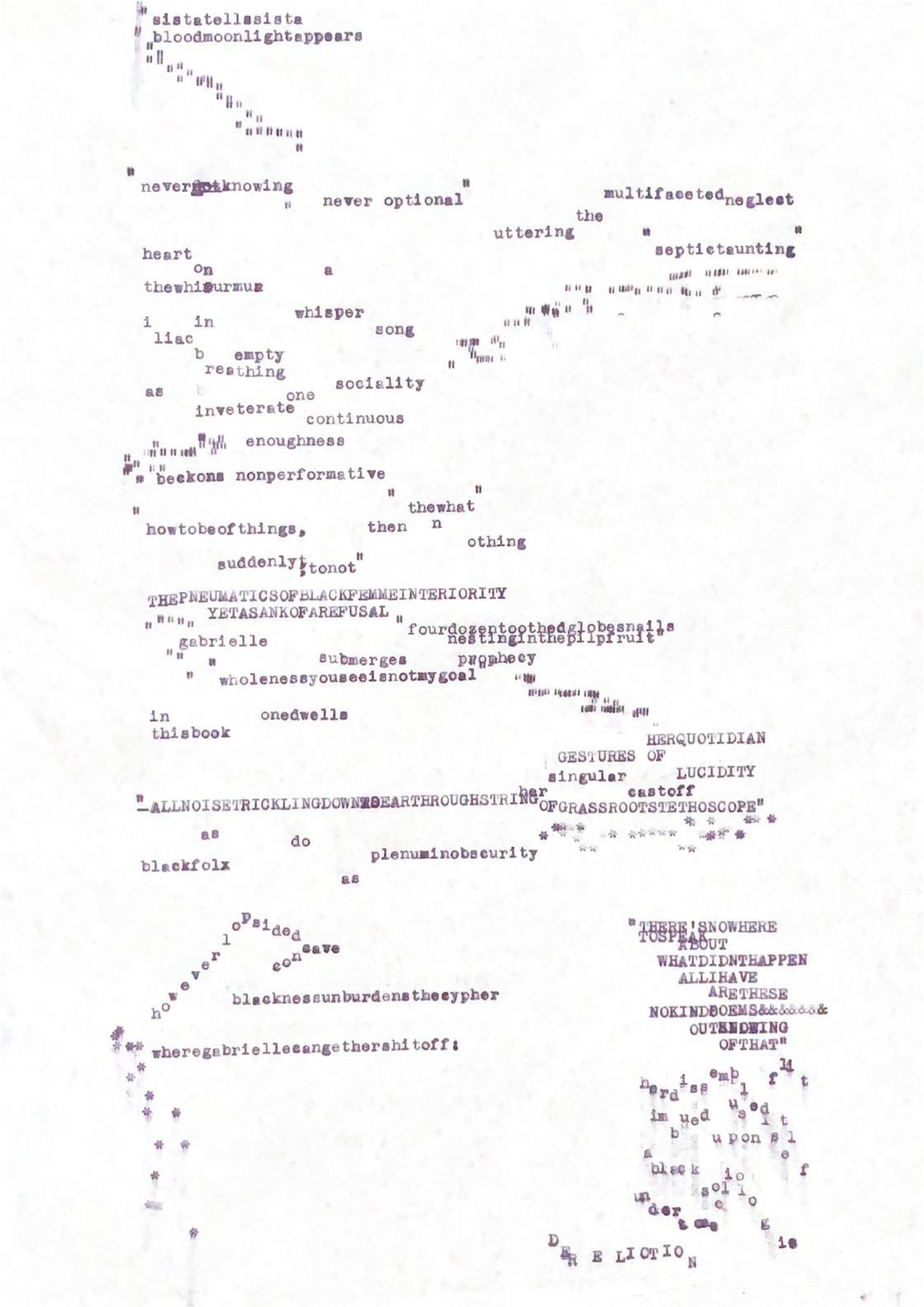

Glück’s decades-long fixation on disjunction, death, memory, and the tension between public and private space reach a crescendo in I, Boombox. He writes to “redevelop / the line break.” The book considers a series of “intentional misreadings” that triangulate between an Imagist sense of ideas in objects (as in William Carlos Williams), an Objectivist self-reflexiveness, and the New Narrative tradition of generative translation and appropriations of language, among other found material.1 The misreadings approximate fantasy and seek pleasure: a rule that revising can only happen in cemeteries, bedding gets pulled out with the soil, a hand gets held at “the edge of the paragraph.” Language serves as the primary vehicle for these interactions: “The / real becomes / real the more / ways you itch the / word.” Glück taps a hole in the membrane of language and widens it slowly, coaxing out surprising depths along the way. He writes, “My mother told / me the stars were / slanting again / intermittently / in a vanished / time. Gorgeous games, / calisthenics / of the real.”

Throughout I, Boombox, the conjunction “or” allows overlapping realities to be true at once, a tactic Glück pioneered in his New Narrative novels that often defy linear temporality. In Jack the Modernist, the narrator poses the question, “How do I mesh modernism’s disjunction with continuity and depth of feeling?” Throughout I, Boombox, the central disjunction relies on a repeated use of the word “or.” In one moment: “Or the flowers / are wiltingly / beautiful, or / he diced of coarse / creating a / separating / consciousness between / house and home.” Here, the modernist urge gets merged—the “wiltingly beautiful” flowers (decaying) evoke depth of feeling, while the split between house and home provides disjunction. Alongside the “or,” Glück’s misreadings—of news headlines, Grindr usernames, song lyrics, conversations, French theory—play with the gap between a lack of continuity and depth of feeling, creating a new logic revolving around the poet’s consciousness at play. For instance: “I hate being / famous for my / tits and never / for my kisses. / My force slips or / goes funny.” While in Glück’s fiction characters tend towards disjunction in relation to time and narrative, in I, Boombox disjuncture takes place syntactically, and, thus, breaks open the spaces between ideas. Ruth Jennison, in The Zukofsky Era, argues that the use of parataxis in the work of Objectivists Louis Zukofsky and Lorine Niedecker produces “revolutionary literacy,” that stringing seemingly unrelated clauses together reveals “absolute interdependence” among subjects across distant times and geographies.2 Likewise, Glück’s parataxis connects political events to the personal slippages of desirous everyday pathology, bridging a dream-like world with the material reality of class struggle.

The lines in I, Boombox, in a Language-y way, seem completely unrelated to one another, refractions of Glück’s unconscious willfully misinterpreting overheard conversations or phone notifications. Glück worked on I, Boombox for over twenty years (ditto his forthcoming memoir, About Ed), gathering misreadings in journals before transplanting them into the poem. This work does not square cleanly with Glück’s novels, or even his other poetry collections, like the lyric Reader. In Reader, Glück is primarily concerned with form—all the work in that collection is titled after schools of poetry, time periods, other poets, and pieces dedicated to writer friends (“A Ballad for Kevin Killian to Read,” “A Myth for Judy Grahn to Read”). While expressions of explicit desire and fear form the basis of Glück’s other projects—and particularly his New Narrative novels—I, Boombox focuses more on developing a sense of play. A collection composed of slippage allows the reader room to examine their own desires, latching onto phrases or ideas that might resonate at a given moment, not unlike the feeling of recalling an image from a dream the next day.

In fact, reading I, Boombox feels like entering a realm of desire, where the poem offers us a new syntactical mode—that of the dream. The poem does not stay in a single dimension, or even on a single thought, for more than a few lines. In this sense, it recalls Zukofksy or Niedecker: the modernist impulse governs, as does an acute and intimate relationship to pleasure. In “Long Note on New Narrative,” a manifesto composed in retrospect, Glück writes, “I experienced the poetry of disjunction as a luxurious idealism in which the speaking subject rejects the confines of representation and disappears in the largest freedom, that of language itself.” In I, Boombox, this descent into language manifests as a form of yearning: “the longing / to be a fragment.” Wanting to “be a fragment” becomes its own form of disjuncture, an unrealized desire within the formal constraints of the poem, which is itself not fragmented. The misreadings reject “the confines of representation” as they stand on their own, contextless, obscuring the speaker’s emotional landscape. And so, pleasure abounds.

Part of the appeal of the misreadings is how we cannot trace them back to their source material. See: “Bumbling / through language, thanks / to innovations / he invented / readers, fatally / registered trademarks.” What was “trademarks” before the word went slant? It is difficult to trace the pronoun “he” back to a person: in the following line, the poem talks of “Cardio-Cowboy” and a “Top Daddy for Ruin.” These and other characters have no desire to present themselves with clarity, and seem to exist mostly in relation to myth and memory, if to anything at all. At other times, the source text is more legible: “A format feeling / comes—the anal / orientation substitute.” Emily Dickinson’s “formal feeling”—a reflection on the shock that comes after immense grief—gets reappropriated. Queerness, here, becomes about an orientation towards a body part, and the feeling is formatted, literally rendered into objecthood. Desire, too, becomes object in I, Boombox: “At the / edge of seventeen / I bravely swallowed / my gulping eros.”

Glück tosses us into a world of merging and morphing realities, where the space between inside and outside collapses, the internal is made external (“open side of my body”), and nudity turns the body into a threshold (“getting / as naked as / we feel wearing / a greed door of / shocking orange”). Domesticity continues to manufacture new modes of relation in the poem as Glück crafts a trinity of death, decay, and marriage. We see it here: “bedding schemes / pulled out the soil.” Then, marriage leads to decay: “Fester quality / following dream / to rave divorce.” And again: “I walk through your / ideas at / night, smattering / lushness wording / buttermilk channel.” Intimacy folds in on itself, as domesticity troubles the notion of the outdoors. A lover’s ideas can be walked through: the “buttermilk channel” takes a kitchen object (buttermilk) and makes it public: a channel—perhaps even the Buttermilk Channel that separates Red Hook from Governors Island in New York City. These moments recall Glück’s lifelong chronicles of cruising, where the private is made public.

Glück has always been fascinated by death—violent depictions of Jesus’s death in Margery Kempe, a parable of men seeking Death in Elements, comparing orgasm to death in his poem “Burroughs.” In Jack the Modernist, the main character considers the space between life and death to be a sexual object, recalling Kathy Acker: “There’s Bob looking up at you, you are a mountaintop view of life and death—jockstrap—metal studs.” But I, Boombox marks a movement in a new direction, where death serves a practical purpose as the conclusion to the long modernist poem. I, Boombox follows the quotidian and consumptive impulses of the life poems that came before it, like bpNichol’s “The Martyrology,” Nathaniel Mackey’s “Mu / Song of the Andoumboulou,” and Zukofsky’s “‘A.’” These poems that include accounts of errands alongside ancestral origin stories, published in many sections over many years, set the pattern for I, Boombox. In this collection, death relates most directly to memory and curiosity, rather than violence or base fear: “The ship’s officer / carelessly relies / on miracle, / seeks disaster / across the wide / estuaries / of death—the rubbed / wool turtleneck / of what he was, / of what he was / in.” Estuaries connect saltwater and freshwater, an entire ecosystem formed in a liminal space. If death is made up of wide estuaries, what lies on either side? The turtleneck holds the form of the officer’s past selves, bridging memory through object. What is the difference between “what he was” and “what he was in”? These questions of selfhood—what is the self, how does the self change in private or public, in thought or dream—abound in I, Boombox.

In Bona Nit, Estimat, a recent piece Glück published in the Paris Review, he returns to many of the themes laid out in I, Boombox. Glück refers to himself as entropic (a term chosen alongside Bruce Boone) while reflecting on friends who have passed, Kathy Acker and Kathleen Fraser. He “de-stories / the distinction / between life / & death,” calling their memories and laughter into the bedroom with him and his husband. See: “I often think about the dead before sleep—saying goodnight to them? Not think about—more like have the feeling of them.” Time collapses. I, Boombox lives in that collapsed, durational place.

- Jean-Thomas Tremblay, in their essay “Together, in the First Person,” troubles the history of this collage mode, considering the line between collage and appropriation.

- Jennison, Ruth. The Zukofsky Era. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012: 203.