As a high schooler, I got introduced to punk and hardcore scenes by catching live shows at a DIY venue in my hometown called The Meatlocker, which looked and smelled just like it sounds. Friends would take me there to catch bands made up of either classmates from school or older, more established musicians, the space glossed with stains and grime, graffiti everywhere your eyes could land, mosh pits frequent and full of hard, sweaty elbows. I had a great time, though I was just the green, still-evolving friend following my cooler, more self-possessed friends then. These friends had the confidence from a young age to go and make space for themselves in punk scenes as black folks, queers, women, and all permutations of these identities. Had Sean DeLear attended my school at the same time as me, he’d have probably been the one in the know who I’d have followed to the good time on any given night, and he’d likely also have led one of the bands playing at The Meatlocker. Reading his 1979 diaries, you can see hints of how deeply inaccurate the framing of punk as white culture over time has been, a point which Brontez Purnell emphasizes in his wonderful introduction. Although the crowd may come across as loudly white and male at times, people like us have always been a part of its core, most especially the boldest of our ilk like Sean. His diaries give the impression that he was fully-formed as a fourteen-year-old, though also deeply his actual age; reveling in the present while being very much of (and from) the distant future.

Throughout Sean’s journals, there’s a great affective sense of what writer and scholar Namwali Serpell calls “black nonchalance”: a way of living in the world that acknowledges disappointment or obstacle and then pivots gracefully past it, refusing to dwell, thanks to one’s innate sense of the bigger picture. An avid cruiser—sex-brained in the most teenaged way possible—Sean frequently details some could-be public sexual encounter that doesn’t pan out, then punctuates with “Oh well” before promptly moving on. I feel concern as I read about his exploits with adults (always, of course, the responsible party in these dynamics), but his nerve and candor keep the pages turning. He expresses a mostly cavalier attitude regarding school: while plenty of suburban fourteen-year-olds might worry about grades more than most other things, he admits his report card one quarter probably won’t look too great, followed by a decisive “Oh well.” Perhaps he’s already sure he’s a star outside the confines of academics,and knows there’s no need to sweat it? And he’s right.

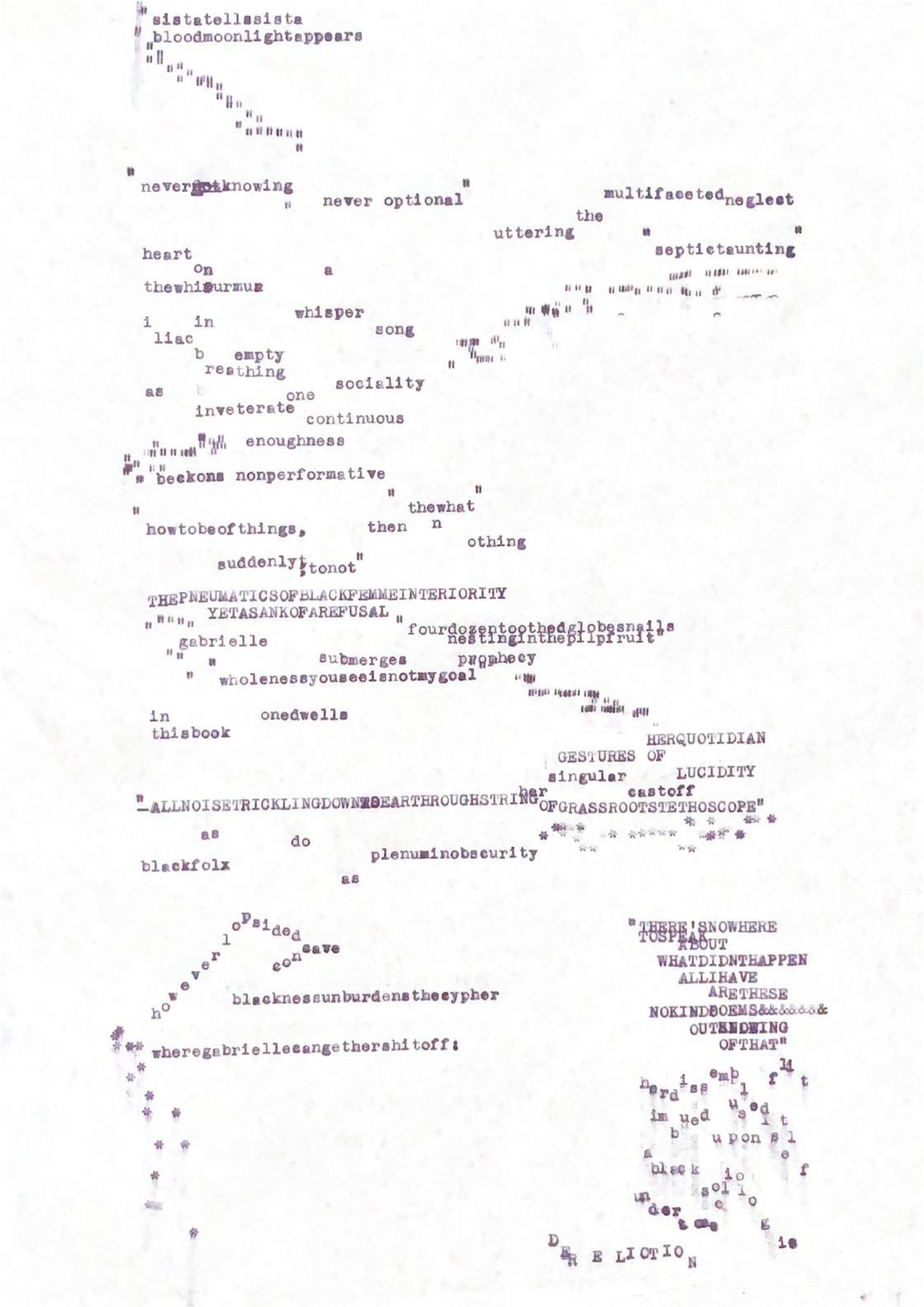

Sean’s ease of being translates, often, to keen emotional maturity. On January 22, 1979, after losing his grandmother, Sean writes:

He’s able to find peace in letting go because he knows through familial wisdom the cruelty promised for black life in the United States—and understands it firsthand, growing up in the very racist, conservative Los Angeles suburb of Simi Valley—and even as he internalizes, in this coming-of-age period, the ways that this cruelty will continuously compound with homophobia in his own life, he unfailingly conveys boundless exuberance for beauty and intrigue in the daily. This is sophistication, I think, akin to Serpell’s analysis—not simply naïveté.

I love reading about his bowling scores and volleyball games and school spirit days, his new and ongoing crushes, his friends’ birthday parties, his frustration with his mother (AKA “the bitch”). He once posits writing a fake suicide note and letting her find it, which prompted an out-loud what a little shit response from me. I love that he loved some of my favorite disco tracks when they were still new, like Donna Summer’s “Bad Girls” and Sister Sledge’s “He’s the Greatest Dancer.” I love his obsession with documentation, evidenced not only by the journaling itself but also by his constant film camera photography at school. And I love this book as an archive of all of the smutty magazines Sean used to buy or shoplift, like His & Hers, Honcho, and Blueboy.

Stylistically, the nearly daily entries tend to follow a similar sequence: what’s up at school, sex and lust, parental drama, maybe a note on something he’s saving up for—like a waterbed—and then “good night.” Within this year of chronicling, Sean more than once notes spotting what he calls “the biggest cock” he’s ever seen: an enthusiast, not unlike a birder or a stamp collector. There’s a gritty, minimalist aesthetic to Sean’s writing that provides real contrast to the polish and pageantry of traditional literary writing, which echoes punk rock’s rejection of mainstream music norms. “Refreshing” and “fun” are the keywords here; it’s the kind of work that might inspire writers to let loose some more in their own practice.

This is a portrait of black gay youth, specifically of a youth who stepped into his agency from early on, a youth who was highly sexually active and would outlive the AIDS epidemic, despite belonging to the exact demographic most overrepresented in positive cases and subsequent deaths—a miracle considering the number of black queers lost to grave government neglect. This book feels like a cousin of the difficult to find Gary in your Pocket, edited by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, a volume of poetry and prose by black queer writer Gary Fisher which includes frank, visceral journal entries from 1977 to 1993 on hardcore sexcapades, desire and isolation, and rage against living with AIDS, among other topics (note: Sedgwick was his professor at Berkeley).

Sean DeLear sadly passed away in 2017, and we’re so fortunate that this book has immortalized his gorgeous spirit. Reading him, reading others’ words about him, and looking at photos of him, I see a friend. I Could Not Believe It sidesteps politeness, respectability, manners, and shame. There is as much revealed directly about Sean’s life and interiority as is left unsaid; generous vulnerability paired with Old Hollywood mystique. It’s propulsive and salacious and would deeply offend plenty of book-banning zealots. That’s true panache!

June 14, 1979: “I did not know I had so many friends but everybody at school likes me almost. If they don’t they would be great actors. I am so nice so why should they not like me you know.”