Destabilized. Destabilizing—as in currently was and still am. In the process of. As in nothing is quite complete, decided, final. Like how Kamden Hilliard said in an interview with Full Stop, “The poem becomes a raw-er vector, consumed, and obsessed with the basic challenge of documentation.” Like how MissSettl inspired me to disrupt my routine of going to my regular library and, instead, try out a new one, to see how becoming unmoored from one institutional tether could propel me into a different space, a different frame of mind, a different net. Like how I canceled all of my feeld dates to read this book aloud in the bathtub with my ears underwater to sense the poem’s sonorities in an echo chamber deeper even than that of my empty studio apartment. I am a divorcee divorcing from myself at that moment. From the language as I have known it. Like how H read Bob Kaufman for the first time and declared, “I didn’t know language could do that.” Or did they say, “I didn’t know language was allowed to do that.” As if language must be granted permission—duh, doesn’t it always beg for permission? This poorest, most illegible of forms? And we propose an advent only for its rejection.

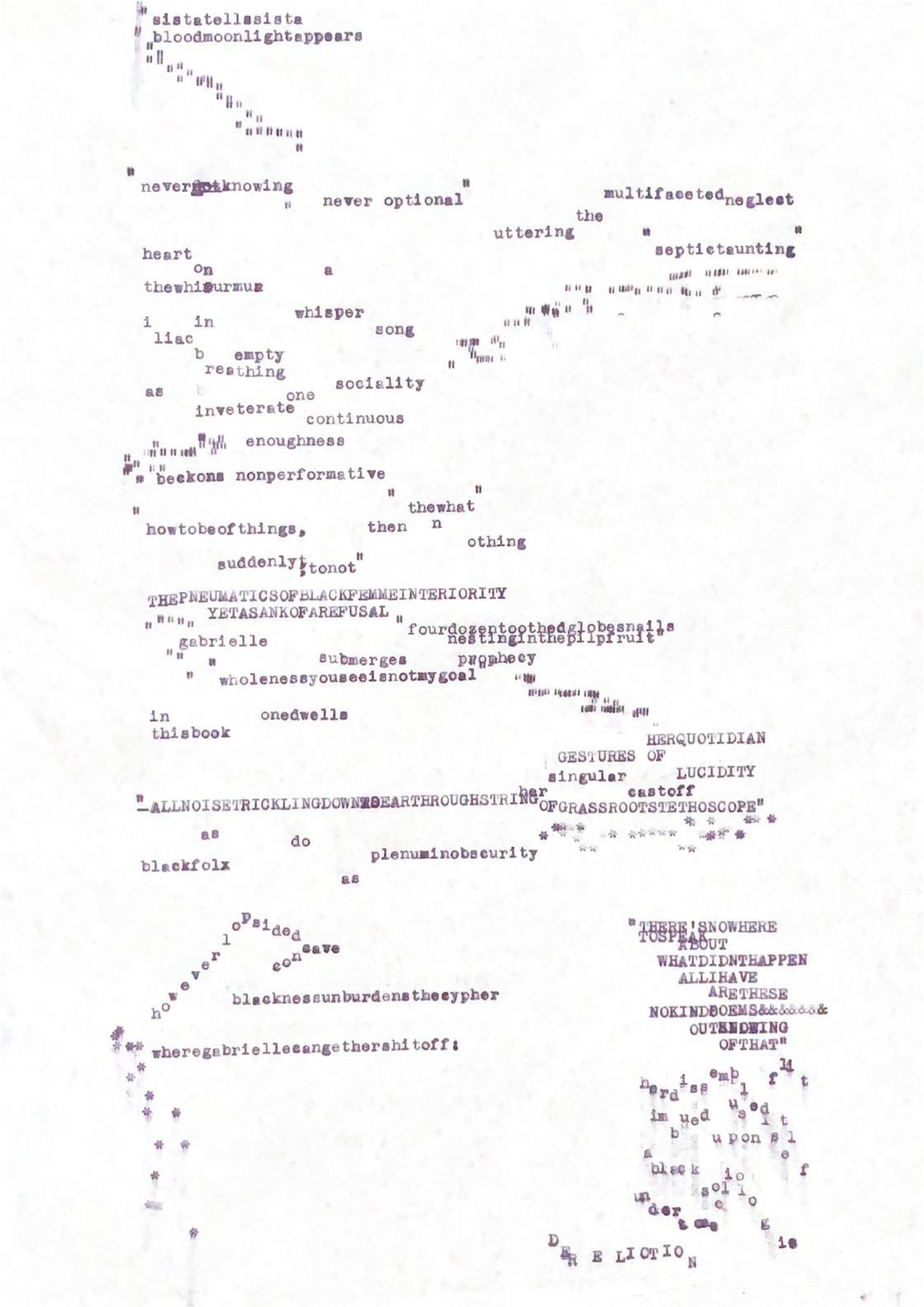

We contort ourselves into convenient boxes only to explode later within our own language. To decompartmentalize all that we embody on any given day (ever-changing sun and moon and cellular combinations):

To become destabilized means to forget what you once knew. Abandon it, even, consciously. “Alas, crisis hot language quandary.” This is the state I am in: “crisis hot language quandary.” Just as in the poem, “BAD PLATE,” it bears repeating: “Crisis hot language quandary.” Like how I forgot my computer charger today. Or did I? Maybe it was a prank played by journal and pen. Journal and pen played a trick on computer for once. As revenge for all the pranks that technology plays on us on the reg.

What MissSettl reminds me: that if there must be a container, let it be one in which to play inside of. That poetry must always open itself up to the infinite capaciousness of play within language. And beyond play—its particularities, its embedded errors, its limitations and its liberatory methods of which illegibility must remain one of its power holds for those of us who must function/survive/thrive within the strangleholds of white supremacist capitalist patriarchy…on the reg. For you to not “get it,” for you to miscomprehend, is a prize. Because this means that you will not manage to co-opt, to capitalize, on that which is meant to remain free and for the people—poetry.

What is it like to read MissSettl? I described it to my therapist as bearing witness to a mental undoing that could only leave my self undone as well. Unraveled. I’ve shared the book with some friends who turned to a page at random to read a poem. I hand it to them and say, “Read one of these out loud to me.” While their reactions are not identical (i.e. universal) there are some similarities. A kind of woah, eyes lit up, giddy laughter, a pull the book away from their gaze, close it for a moment to process what it is that they have just read kind of reaction. My therapist wanted to know how the book is affecting me—I told her that I’m existing in that moment I so seldom reach, of language being pushed further, beyond its perceived extremes. Like how B has told me that there’s nothing quite like being elbow-deep inside of someone’s anus. I have yet to try this but the poems encourage me to do so. Go further. To go ass deep. I suppose I’m having an experience akin to what Hilliard experienced when they first read Lighthead by Terrance Hayes. They said that upon reading that book, “those neat barriers which I’d arranged around in my head, demarcating what is and is not fit for poetry… I realized those barriers were very mean-spirited and dangerous, as most barriers are.”

Upon reading MissSettl I have come to accept that prior to this, I was walking behind language, following it, straggling behind it like a stalker. Then it abruptly stopped, turned around, smiled and waved at me, slightly mischievous, slightly sardonic. Letting me know that it saw me, had felt my presence all along, and could I please either stop following it, walk alongside it, or choose my own path, PLEASE???

At first I wanted to be angry with the book for calling the confines of my own neat barriers to my attention in such a distinct way. A glaring line of José Esteban Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia was shining back at me, blinking like a club’s neon sign: The here & now is a prison house. But how could I be angry at something so full of love? So brimming with permission granted to be unacceptable, miss comprehensible, completely illegible?

I think it’s only fair that I’m afraid to write this review (can we use another word, PLEASE???) of a book written by a poet who has said, “I do resist the sentence, the container which is supposed to hold one idea.” It is no wonder (but it is a wonder!) that Hilliard has also said that “a poem is a kind of thought… a genre of thought.” What is the difference between thought and idea? What does it mean (what are your expectations) when you ask someone the question: What are you thinking? How to transmute the thought into verbal/linguistic cues.

“I would love to hear your thoughts,” has always been one of the most erotic sentences to me—and here in these poems, I hear thoughts! So loudly and so singularly, specifically because of Hilliard’s refusal to conform to “an English operated under white supremacy,” specifically because they are able to “express the full intimacy” with lines like:

The vulnerability of sharing something. Anything. “Hu can show a little and live through the exposure?” How it makes you feel without any certainty that the other will be able to feel what you felt or at least understand how/why it is that you feel this way even if it’s not their own lived experience. The fear that revealing differences could, in fact, produce the opposite effect of connection, it could be the opposite of life-affirming—it could, in fact, result in your death.

This is the repeated risk that Hilliard takes with their poetics. This is life and/or death poetry. This is love poetry to a most infinite degree of love pushing it/us beyond its/our known capacity.