Mise en scène: Valerie Hsiung’s virtuosic, book-length psychedelia-against-empire—a poetics of obfuscation measured out among heteronyms, a devastating excavation of memory as linguistic matter, performatively picking the scab of phonic displacements, fleetingly renderable while impossible to untangle. “This was how I got my voice,” Hsiung writes. “In memory, a germ becomes a self, / a capsule, a body eventuated in worms and flies and chunks.” With The Only Name We Can Call It Now Is Not Its Only Name, the artist resettles herself at the innominate farm, site of civilization posited as original wound. From here we disembark—artist, reader, language—towards an orthography of half-forgotten names & murky violations, “[e]ar pressing up against muddy rock and all.”

The endeavor of Hsiung’s ongoing poetic process, while maximalist in breadth, here takes on durationally fragmented variations of oscillating syntactic rhythm, asking into the always-full hole of history questions barely articulable, whose teasing is made possible in the space of ongoing performance (text). She chases the problem at the heart of naming, which language—distributed across subjects with discrete material half-lives—renders first as horror, then as art. “Can we explain mysterious acts of self-mending under conditions as cold as this?” Hsiung asks, any possible responses clogging both artist’s & reader’s ears with muck.

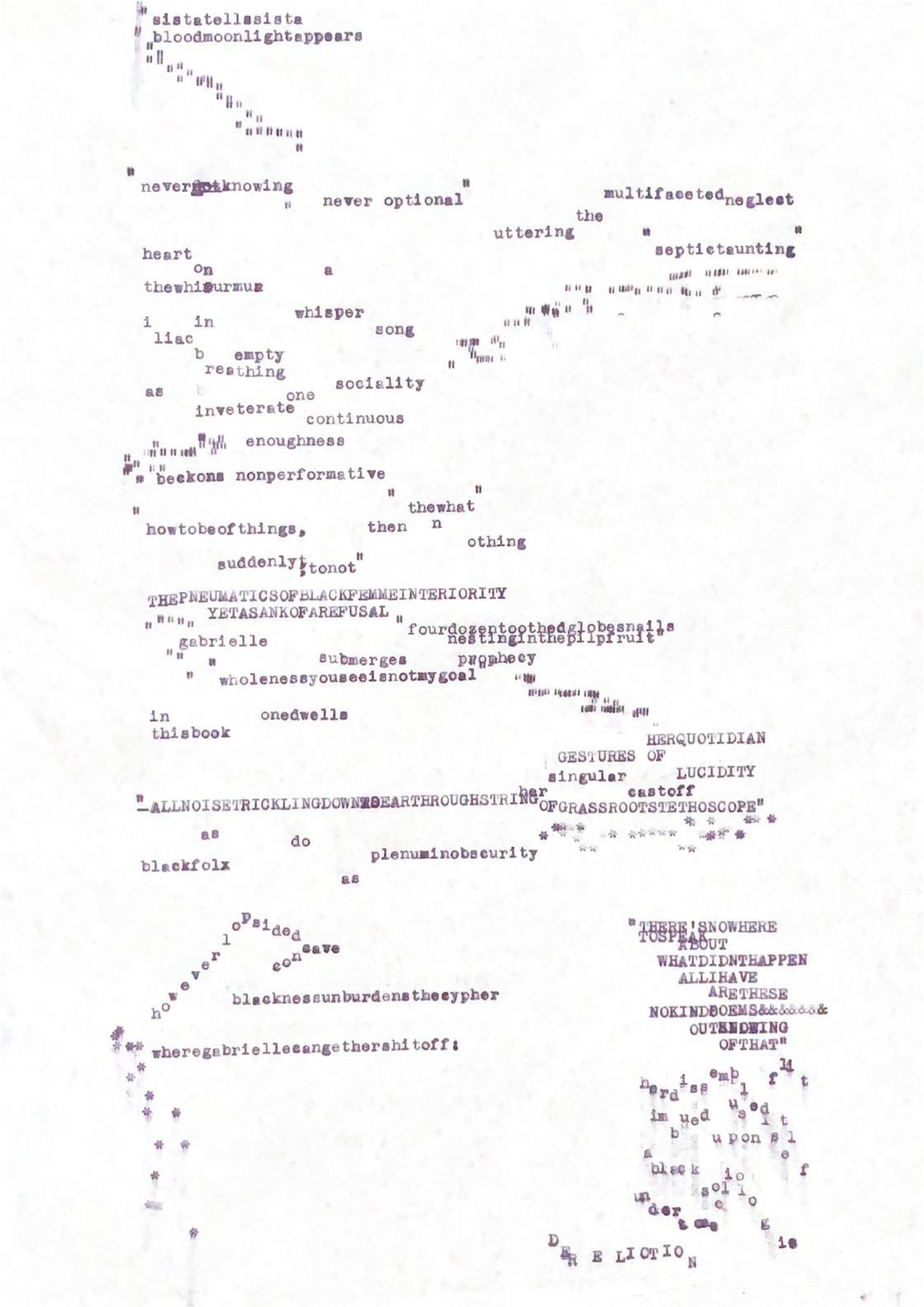

Taken as an ongoing whole, the rigorous arc of Hsiung’s work feels immediately improvised & obscure. Prose gives way to crisp lineation, pulsing with charm & tragedy in a tenor all her own. Hsiung possesses a thoroughness of vision & technique, as reckless as it is dazzlingly realized in a space between poetics-as-such & performance art. Hers is a poetics of not-quite-poetry, not-quite-writing. In a recent BOMB interview, she states:

If my writing has been composed of dislocations, it’s because the material conditions of my life have been composed of dislocations. What strikes me in all of these dis-es is the fact that they are all standing against assimilation and consumption. The disabled body: the complete dissolution of the structure for understanding assimilation’s capacity, consumption’s uptake. The disobedient body prevents the system from working.

With The Only Name, the reader encounters something close to the total risk of being. Through the conduit of historical materialism—upheavals of displacement reorienting a person or people’s total experience of grounding—mother tongues & discrete customs of the body must epistemologically contort. Regardless of whether the artist would pose her stakes as such, the book deals in bitter roots (an empire’s obliterative wake), chronicled in their own particular languages.

Interrupting the sometimes prose, often aphoristic formal logic of The Only Name’s text, Hsiung composes, in stringy lines of “legible” poetry, the nebulous question of her book-length experiment:

I am afraid

without exaggeration

what I say

is what I write will

send the people I owe

something to

to prison

to their deaths

to their hidings

so I hide a something

chanting can hide a something

and maybe

if I hide enough

like the wind hides itself

enough will make dot to dot make

a point

Hsiung’s work conveys her deep trust in the reader’s ability to push themself dexterously towards the non-destination that is language’s object—being—while simultaneously doubting & trusting in language’s material ability to do so. “I guess I want the performance to only be an arrangement of the voice, and I want the voice to talk about what the letters are doing.” Try this approach, live inside it, witness / feel the resonance of all time.

I find it peculiar that K began asking then about my mother’s origin and the ordinariness of intergenerational trauma as it connects to mother tongue and political exile. In the way that K found it difficult to pacify my vernacular-less voice on the phone recording I sent K with the voice in person that I employ—I find it difficult to locate why my mother’s voice matters, at first, and then, now, as I’m speaking to you, it’s very palpable on an almost instinctual level why it matters. Why does it matter.

Exceeding the formal limits & logic of a more conventional collection, The Only Name offers instead a fully realized poetics of gestures—“[h]ands, lips, faces, bodies, the loving bodies of the ones I love,” limbs that might arise from humus (the page’s double). In engaging the embodied / performative nature of Hsiung’s latest work, I find myself eager to situate it within a constellation of other consummate experimentalists with the “stuff” of language––Aristilde Kirby, Cody-Rose Clevidence, Angel Dominguez, as well as Indigenous scholar Tiara Roxanne’s performance-based invocation, “I cannot decolonize my body.” Ghayath Almadhoun makes a literal appearance (his work haunts similar spaces), Hsiung stating flatly the necessity of performance poetics in excavating lines to find the level of letter, “...because of the whole history of socio-economic systems which have pilloried and governed women artists and often kept them, us, from freely living their, our, own lives… until perhaps fairly recently. And even then, it feels… often tenuous?”

Throughout the duration of The Only Name We Can Call It Now Is Not Its Only Name, an image is subtly recalled: that of the ear-hole pilloried by mud, grounding & confounding any subjective stability we may find in, or seek through, language. “Ear pressing up against muddy rock and all.” I am reminded of Ana Mendieta’s Mujeres de piedra (Stone Women), a site-specific land art installation in the caves at Escaleras de Jaruco, Cuba, marking a point in the artist’s unification of body & earth as inseparable, mutually-formative subjects. Though differing in their chosen mediums, Hsiung, like Mendieta, creates in the mode of land art. The farm, recurring site of dismembered demarcation in the book, is a place that both mothers & is barren of mothers, these two states threaded together in language to make histories. “It was her who taught me how to remove mud from the ear,” Hsiung writes, the subject here being earth or diasporic mother, heteronyms as nuclei in an impossible attempt to unravel time with tongue, breath, notation, & dissipation.

We flirt, too, with the notion of what it means to keep sending parts of inwardness out into the world and the world is never empty totally because of this.